Virtual Influence v2

Kelton Rhoads, PhD

Introduction

Influence in the virtual world is topically situated between leadership skills on the one hand and negotiation skills on the other. Modern business and government leaders have been attracted to the allegiance and performance rewards that result from leading by inspiration and persuasion rather than by dictation and threat. Thus, influential styles of leadership are carefully cultivated by today's leadership elite. But social-savvy leadership brings with it the need for constant and ongoing negotiation. In a world where hearts and minds are won rather than commanded, accommodation and negotiation are the coin of the realm. Common to both competent leadership and negotiation lie a complex set of influence skills.

While social scientists have investigated the topics of influence, persuasion, and indoctrination for a half century, the ability to use computers as a persuasive channel is a relatively new phenomenon. As more and more social transactions occur via computer mediation (CM), online activities from shopping to negotiation still abide by fundamental human rules of interaction-with a few twists. In the following summary, I present three phenomena that distinguish online influence from face-to-face (FTF) influence, followed by four established principles of influence whose effects are multiplied in the virtual world.

In With The New

CM has brought with it novel abilities to furnish decision makers with multiple options, to allow negotiators to reach fairer judgments, and to allow anonymous communication.

Creativity & Multiple Options

Professional negotiators know that negotiating sets of options, rather than negotiating single points or sequences of points, makes it more likely that a negotiation will be settled to the satisfaction of both sides. In addition, creative solutions sparked by CM can sometimes cause opposing sides to move forward when "siege mentality" has set in and has caused opposing sides to focus on a limited number of salient issues and solutions. Since creativity and flexibility of thought is central to creating acceptable settlement solutions, groups that negotiate via CM have a creative advantage because they are likely to generate more, and more creative, solutions for mutual benefit (Croson 1999).

Just as CM brainstorming has been shown to be consistently superior to FTF brainstorming, CM group negotiations have the advantage of avoiding process losses, conformity pressures, and salience traps. Process losses occur when individuals stop thinking to listen to others, which is much less likely to occur in CM communication, where people can "listen" at their choosing and need not be distracted from generating solutions. Conformity pressures occur when an authoritative individual, or group of individuals, deliver an opinion, causing others to "go along" and stop contributing solutions of their own (El-Shinnawy & Vinze 1997). CM has demonstrated a marked decrease in conformity in a number of experiments. Salience traps cause the first solutions generated to become focal, causing subsequent discussion time to be spent debating the pros and cons of the first proposals, rather than on the generation of new proposals.

Recommendation: Consider using virtual negotiation procedures only when numerous creative solutions are the key to moving forward, and when you want to avoid conformity pressures when reaching a solution.

Conformity pressures at work in a FTF setting.

One of the fundamental human values (and particularly among the politically liberal) is equality. There is evidence that CM negotiated solutions can be more fair, since more people can voice their opinions, and voice them at equivalent length in CM. Additionally, some researchers believe that dominant personalities have less control online (Kiesler, Siegel & McGuire, 1984) which would make sense where more people participating in a conversation could flatten a hierarchic structure. On the other hand, the acknowledgment of other peoples' views tends to decrease in CM, as people concentrate on expressing themselves (Sproull & Kiesler 1998). The opposite holds true for FTF negotiations, where the socially adept are more likely to capture attention and achieve their ends through superior social skills. But confrontational FTF tactics (demanding immediate answers, demanding "yes/no" answers, and flustering the opponent) don't work online. While email negotiations have been observed to produce somewhat more integrative win-win solutions, that same study observed fewer pairs of CM negotiators who were able to reach an agreement, compared to FTF negotiators (Croson, 1999). We can surmise that CM negotiations inhibit skilled negotiators and those who are willing to confront an opponent aggressively, giving the advantage to the less socially skilled and nonconfrontive participants.

The ability of minority members to influence is not, however, improved through CM. While minority opinions are more easily expressed in CM communications, CM also appears to reduce minority influence. Since minority influence is usually informational in nature (Moscovici 1985), it is at a disadvantage in CM because information is less likely to register or be remembered in CM than in FTF. People are simply less responsive to each other's ideas in CM (Kiesler, Zubrow, Moses, Geller 1985). In one CM study, a participant (Member "C") was identified as low status. Member C attempted to make his case via CM and FTF, and made his appeals to groups of mixed high & low status individuals as well as to groups of uniformly low status individuals like himself. The only condition in which Member C could make himself heard was in the FTF/low-status condition. In reviewing their results, the experimenters concluded that not only were low-status members rendered less persuasive, but that ". . . CMC reduced perceived influence of all group members, regardless of status." (Hightower & Sayeed, 1995). In other words, CM suppresses influence skills to a point where everyone is working at a disadvantage. While minorities tend to express arguments more frequently and more persistently in CM compared to FTF communication, they are in fact more effective when they communicate FTF (McLeod et al, 1997). It appears that politeness norms, which cause majorities to give floor time to minority opinions in FTF situations, are ignored online as participants concentrate on expressing their own opinions. Large numbers of advocates and large numbers of arguments, rather than quality arguments, tend to prevail in CM discussions, leaving even strongly argued minority positions at a disadvantage.

Recommendation: Consider CM when attempting to capture diverse points of view, or when you intentionally want to flatten a hierarchy in order to achieve a solution. Unskilled negotiators should consider negotiation via CM but skilled negotiators have an advantage with FTF. Those with minority opinions should avoid CM when attempting to influence a majority.

Anonymity

Anonymity has received considerable study in the CM literature because of the nature of online communications--email, newsgroups, and websites all allow the author to remain anonymous. While technology has created the opportunity to communicate with millions and yet remain anonymous, the human reaction to anonymity has been well documented before the advent of CM, and its effects persist in the new environment. Anonymity weakens normative pressures, one of which is conformity--which explains overall reductions in influence for CM. Another norm is one's commitment to previously held positions. Studies of CM decision making have shown larger shifts in opinion, compared to FTF, and researchers hypothesize that anonymous participants feel psychologically free to abandon previously held positions in CM (Kiesler, Siegel & McGuire 1984). But neither does anonymity allow recognition. Researchers have noticed that while anonymous CM communications yield more arguments overall, those arguments are of dramatically lower quality. Both the validity and novelty of persuasive arguments suffer in anonymous CM discussions. The researchers posit that people don't put the effort into making good arguments when they can't get credit for making them (El-Shinnawy & Vinze, 1997). Of course, anonymous input is disregarded by most people as simply lacking credibility, so investigations into persuasion under conditions of anonymity have few practical applications.

Recommendation: Allow anonymity to reduce normative pressures such as conformity and commitment to previous positions. You are more likely to get people to reverse their previous positions if they are allowed to vote anonymously. However, anonymity does not help generate quality arguments when discussing a case.

Long Live the Principles

While CM communication presents a number of new and interesting twists on human communication, CM also reinforces a number of well-established principles of influence. These include Social Presence, Communication Frequency, Commitment & Consistency, and Salience Effects.

Social Presence & Spheres of Influence

Most people read Stanly Milgram's research of the 1960s and 1970s as a commentary on conformity in the face of an authority figure. As you may recall, Milgram found that approximately two-thirds of the population was willing to electrocute a stranger on nothing more than the verbal direction of an authority in charge of an experiment. But Milgram himself was impressed with another finding in his series of experiments. Milgram proposed invisible fields of influence that surround humans, which he called "Spheres of Influence." This may sound like an X-file episode to the modern reader, but his research showed that people were inclined to obey the person to whom they were closest. If subject B were placed between persons A and C (who made opposing appeals), B would be more likely to obey the most proximal source, other factors held constant. Our social presence appears to operate like a "Sphere of Influence," strongly affecting those to whom we are nearest, and falling off in potency as distance separates us from our influence target. Milgram's classic research appears to hold for CM communication as well.

FTF negotiation allows mutual persuasion processes to occur, and settlements are more likely when people negotiate in close proximity to each other. Many studies of CM, on the other hand, have found increased resistance to conformity pressures, more objective reasoning, and decreases in interpersonal attraction among members communicating via CM. (El-Shinnawy & Vinze, 1997; Siegel et al, 1986; Kiesler et al, 1984). Some studies have shown eight-fold increases in confrontation in CM communication, compared to FTF (Sproull & Kiesler, 1998).

Consider the following study of cooperation between subjects playing a dilemma game: if the subjects were isolated, a 41% median cooperation level resulted. If subjects could see but not hear each other, cooperation rose to 48%. If subjects could hear (that is, communicate verbally) but not see each other, cooperation rose further to 72%. If subjects could see and hear each other, median cooperation reached 87% (Wichman, 1970). Another gaming study examined the results of a buyer and seller bargaining over the price of a company. When the negotiation was conducted in writing, 41% of the negotiations ended in a lose-lose or "no agreement" scenario. However, when negotiating FTF, only 5% of the negotiations resulted in the same impasse (Valley et al, 1996). While some reports of reversals and nonsignificant differences between FTF and CM negotiations exist (see Moore for discussion), higher impasse rates appear to be the rule for CM.

Indirect evidence of conformity pressure reduction in CM comes from research showing that women show lower amounts of attitude change when communicating via email than do men (Guadano, 1998). This is notable because reviews of the persuasion literature have found that women are, on the average, somewhat more influenceable than men, particularly in social situations where allowing one's self to be influenced increases group harmony. Online, in the absence of strong social pressure, at least one study has found women to be even less influenced than men, leading us to suspect that normative pressures toward conformity and harmony are attenuated online.

Recommendation: If you need to settle an issue quickly, meet FTF. If you wish to enhance people's resistance to conformity pressures, meet online. Additional enrichment of the medium (for example, using video instead of email) will increase the likelihood of obtaining an acceptable solution, and maintaining favorable social relationships.

Communication Frequency

The persuasive value of frequent communications is well-established in the influence literature, with investigations of communication frequency extending back to the behavioristic era. To the extent that CM can increase communications that are positively received, CM can prove to be an effective tool of influence. The basis of comparison, "Compared to what?" is the all-important question. If CM replaces FTF communication, then a reduction in the ability to influence can be expected. However, if CM increases otherwise infrequent or non-existent communication, it is relatively more effective. (The reader is justified in finding the previous observation to be so obvious and commonsensical that the statement of it is irritating.) In a statistical meta-analysis of dilemma experiments from 1958 to 1992, Sally (1995) found that communication was the most powerful determinant of cooperation in experiments over the period reviewed, and increased cooperation by approximately 40%. This effect was supported by a trial in a CM experiment conducted by Kiesler, Sproull & Waters (1996). In the third trial of their gaming experiment, the researchers suspended discussion of solutions (and thereby verbal commitment as well). Cooperation dropped sharply across all conditions of the experiment in this third trial.

Recommendation: If you can't meet FTF, be certain to compensate by increasing the frequency of CM communications.

Commitment

One of the fundamental drives within humans is the desire to remain consistent with one's previous statements, positions, and actions. Humans find it embarrassing to be inconsistent, and have little tolerance for inconsistency in others. We have no compunctions in voting our public servants out of office for changing a stance on an issue. Humans want to be, and to appear, consistent (Schlenker, 1985; Tedeschi 1981). And humans are more likely to remain consistent with their commitments if they have made voluntary, active, and social commitments to do so.

The nature of social commitment appears to extend to computers. People do, after all, respond socially to non-humans--promising their dogs to go for a walk, reassuring their alarm clocks that they intend to get up, and cursing their computers when they crash. In a fascinating study conducted by Kiesler, Sproull & Waters (1996), the researchers arranged for subjects to play a prisoner's dilemma game with either a human or a computer partner that interfaced with the subject textually. (Subjects were aware that the computer was programmed in its responses, and that the computer was not merely controlled remotely by a human.) In this simulation, participants had to choose to cooperate or compete. Cooperation brought smaller gains spread out over a longer time, whereas competition resulted in large, immediate gains if the subject "fooled" the partner into cooperating while the subject himself competed. The majority of subjects proposed to cooperate with their human or computer partners. The question was: How many subjects would actually choose to cooperate and not compete, given that the choice to compete brought immediate large rewards? While 94% of those promising cooperation to a human partner kept their promises, an amazing 90% of those promising cooperation to a text-based computer partner kept their promises. The researchers raised the obvious question, "To whom is the commitment made?" The argument could be made that when people make commitments, they are going on record with themselves rather than with others. It would be difficult to understand high levels of commitment to a computerized partner, unless one took the view that people had an unprecedented anthropomorphic relationship with their silicone-based significant others.

Recommendation: Having people make commitments via CM remains an effective influence tactic. The most enduring commitments are made voluntarily, actively, and socially, and even commitments to a computer can dramatically increase compliance.

Salience of Cues

When theorists in the '80s and '90s conjectured about how the internet could change the nature of human communication, power relationships, and the working world, many academicians divined a rosy future. Some declared that the internet would liberate the individual from group influence; others foresaw a new era of decentralization, empowerment, and autonomy where influence flowed up rather than down the traditional hierarchies. Still others went further to predict the end of tyrannical hierarchies, the decline of authoritative influence, and the dawn of a new age of communicative equality. Academia was abuzz with the possibilities, but when the data came in, it had a sobering effect on the party.

Recent research indicates that status differences don't vanish online, as visionaries had hoped. High-status members have been found to participate more and to continue to be more influential in CM, as well as FTF. This effect has been observed regardless of whether the high-status member took a majority or a minority position, and regardless of whether the high status member was identifiable or anonymous (Weisband et al, 1995)! But when CM allows status information to be conveyed, status effects persist.

While CM blocks nonverbal cues, it doesn't eradicate social category information when it is supplied. CM communication is still bounded by roles and relationships, especially where relationships are long-term and consequences are palpable. Where CM undermines established social relations, it is resisted--usually successfully--by those in power. While interpersonal cues are reduced, the role, status, category and membership cues that remain become more rather than less important. Status information provided in CM can perpetuate rather than reduce status effects. (Sproull and Kiesler, 1991; Spears & Lea 1994; Hollingshead, 1996).

CM appears to increase stereotyped and biased responses to unknown others; subjects do not (and sometimes can not) suppress social cues just because they're communicating online. When less social information is available, that information takes on a larger role in shaping cognitions. For example, in a negotiation game conducted with female subjects, women became less exploitive and more cooperative when they discovered their online partner was female rather than male. This result caused the researcher (Matheson, 1991) to conjecture that female stereotypes of cooperation were activated by gender information, which would not have produced such large effects in a FTF setting where other cues were available.

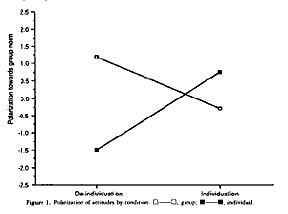

In a related study, subtle labeling tactics resulted in significant effects in the CM setting. Subjects in this experiment were informed that they were "part of a group" in one condition, or were "a collection of individuals" in the second condition. The salience primes were highly effective for subjects who were isolated from each other. Those who were told they were "part of a group" showed judgment polarization that converged on the group norm. Those who were labeled "individuals" showed displacement away from the group norm when making judgments. The priming effect was not as strong for subjects who were in the same room and could see each other, which indicates that subtle social cues are magnified when people are remote and communicating via CM. (Spears, Lea & Lee, 1990).

A (poor) photocopy of the crossover interaction found by Spears, Lea & Lee, 1990.

The defining phenomena of CM is the fact that only a portion of the information available in FTF can "make it through" to the audience. This attenuation of information is responsible for many of the interesting results we see in CM communication. The reduction of social cues in CM may be like "threading a camel through the eye of a needle," but when it comes to status information, it appears the camel is able to make it through nonetheless.

Recommendation:

Since less data is transferred via CM, the smaller amount of

data that is conveyed takes on increasing importance in determining

people's judgments. Subtle labeling tactics can have large effects;

use these to your advantage by applying positive lables to your

virtual team members and their activities. Status information

becomes important--CM can perpetuate status effects. Finally,

CM forces people to rely on their existing biases, prejudices

and stereotypes, so don't expect people to lay these aside when

interacting online.

Bibliography

Croson, R. (1999). Look at me when you say that: An electronic

negotiation simulation. Simulation & Gaming, 30, p. 23-37.

El-Shinnawy, M. and Vinze, A. (1997). Technology, culture, and

persuasiveness: A study of choice-shifts in group settings. Int.

J. Human-Computer Studies 47, 473-496.

Guadagno, Rosanna. (1998). Unpublished manuscript.

Hightower R & Sayeed L. (1995). The impact of computer-mediated

communication systems on biased group discussion. Computers in

Human Behavior, 11, 33-44.

Hollingshead, A. (1996). Information suppression and status persistence

in group decision making: The effects of communication media.

Human Communication Research, 23, 193-219.

Kiesler S., Zubrow, D., Moses, A., & Geller, V. (1985). Affect

in computer-mediated communication: An experiment in synchronous

terminal-to-terminal discussion. Human-Computer Interaction,

1, 77-104.

Kiesler S., Siegel J., and McGuire T. (1984). Social psychological

aspects of computer-mediated communication. American Psychologist,

39, 1123-1134.

Kiesler Sara, Sproull Lee, & Waters Keith (1996). A Prisoner's

Dilemma Experiment on Cooperation With People and Human-Like

Computers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, January

1996 Vol. 70, No. 1, 47-65.

Matheson, K. (1991). Social cues in computer-mediated negotiations:

Gender makes a difference. Computers in Human Behavior, 7, 137-145.

McLeod, PL; Baron, RS, Marti, MW, & Yoon K. (1997). The eyes

have it: Minority influence in fact-to-face and CM group discussion.

JAP 82, 706-71.

Moscovici, S. (1985). Reference missing.

Siegel, Jane; Dubrovsky, Vitaly; Kiesler, Sara; McGuire, Timothy

W. (1986) Group processes in computer-mediated communication.

Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes. 1986

Apr Vol 37(2) 157-187.

Spears R, Lea M, & Lee, S (1990). De-individuation and group

polarization in CMC. British Journal of Social Psychology, 29,

121-134.

Spears R and Lea M. (1994). Panacea or Panopticon? Communication

research, 21 (4), 427-459

Spears R, Lea M, & Lee, S (1990). De-individuation and group

polarization in CMC. British Journal of Social Psychology, 29,

121-134

Sproull & Kiesler, (1991). Connections: New ways of working

in the networked organization. Cambridge: MIT press.

Straus SG and McGrath JE. (1994) Does the medium matter? The

interaction of task type and technology on group performance

and member reactions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 87-97.

Copyright © 2002-05 by Kelton Rhoads, Ph.D.

www.workingpsychology.com

All rights reserved.

Adherence advertise advertising arguing argument argumentation attitude attitude change belief campaign Chaldini Cialdini communicate communication compliance comply conform conformity. Consultant consulting course courtroom credibility credible cult cults debate decision making education emotion essential influence executive education executive programs Franklin Covey influence. Influence at work influencing Kelton Rhoads Ken Blanchard law leadership leadership training legal likability management management market research marketing mind control motivation. Obedience organizational services personality persuade persuasion persuasive political political consulting politics polling principles of influence professional services program promote. Promotion propaganda psychological persuasion psychological research psychology psychology of persuasion public relations questionnaire reinforcement reputation research rhetoric. Rhetorical Rhoads Rhodes Robert Cialdini sales sampling science of persuasion sell selling small group research social influence social psychology spin statistics Steven Covey strategy survey technique Tom Peters trial voir dire workshop. Adherence advertise advertising arguing argument argumentation attitude attitude change belief campaign Chaldini Cialdini communicate communication compliance comply conform conformity. Consultant consulting course courtroom credibility credible cult cults debate decision making education emotion essential influence executive education executive programs Franklin Covey influence. Influence at work influencing Kelton Rhoads Ken Blanchard law leadership leadership training legal likability management management market research marketing mind control motivation. Obedience organizational services personality persuade persuasion persuasive political political consulting politics polling principles of influence professional services program promote. Promotion propaganda psychological persuasion psychological research psychology psychology of persuasion public relations questionnaire reinforcement reputation research rhetoric. Rhetorical Rhoads Rhodes Robert Cialdini sales sampling science of persuasion sell selling small group research social influence social psychology spin statistics Steven Covey strategy survey technique Tom Peters trial voir dire workshop.